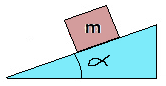

Box on an incline

A box with the mass 2kg is resting on an incline. The task is to determinate the resulting force given an angle of the incline.

When calculating with forces in this example we will use force vectors. This way we can add and subtract different forces together. We can also scale a force with a scalar.

\[ \dot g = gravitational\ acceleration \]

\[ m = mass\ of\ box \]

We scale the gravitational acceleration vector with the mass of the box to get a vector representing the gravitational force.

\[ \dot F_{g} = m \cdot \dot g \]

A unit vector that we get from a radian \(a\).

Force against the incline from the box we denote as \(\dot F_{\perp}\). Since the force is perpendicular against the incline of the surface, we need to create the unit vector for \(\dot F_{\perp}\) by adding \(-(pi/2)\) radians.

This vector we then scale up, with the magnitude of the gravitational force multiplied by \(cos(angle)\), which gives how much the gravitational force that affects \(\dot F_{\perp}\).

There are two edge cases. If the incline is flat, it means the incline has the angle 0, and \(cos(0) = 1\), which means \(\dot F_{g} = \dot F_{\perp}\). If the incline is fully tilted however \(\frac{\pi}{2}\), it means that \(cos(\frac{\pi}{2}) = 0\) and the gravitational force on the box does not result in any force against the incline.

f_l_ :: Vector2 Double -> Angle -> Vector2 Double

f_l_ fa angle = scale ((magnitude fa) * (cos angle)) (angle_to_unit_vec (angle-(pi/2)))The normal force \(\dot F_{n} = - \dot F_{\perp}\) supporting the box from the incline:

The \(resulting\ force\ \dot F_{r}\) is then the normal force from the incline plus the gravitational force. \[ \dot F_{r} = \dot F_{n} + \dot F_{g} \]

We have now determined a way to get the resulting force from a given angle. Below we show how we can use it.

With the use of a rounding printer (defined last in this example) we can round the output.

Here we can see, that \(\dot F_{r}\) on the box is pointing down-left in the sense of a coordinate system. To know it’s magnitude, we can do:

Or with rounding:

Now we try to tackle the problem with friction:

\[ F_{friction} = \mu * F_{normal} \iff \mu = \frac{F_{friction}}{F_{normal}} \]

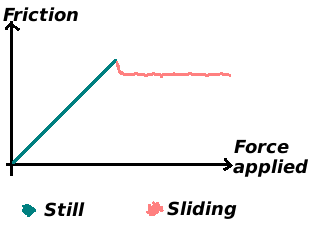

There are two different kinds of friction. One where the object is standing still on the surface, and the other where the object is sliding on the surface. In the case where the object is standing still, it remains still until the force applied on the object is greater than the maximum possible friction between the object and the surface. Once that level is surpassed, the object starts to slide.

When the object is sliding the maximum friction between the surface and the object is slightly less, as illustrated in the figure below.

\[ F_{static\ friction} = \mu_{static} \cdot F_{normal} \] \[ F_{kinetic\ friction} = \mu_{kinetic} \cdot F_{normal} \]

Given that we know if the box is already moving or not, we can chose the corresponding friction constant and calculate the friction force between the box and the incline. The direction of the friction force will then be in the opposite direction of the resulting force without friction, which we determined in the previous section.

We will use a type definition to clarify parameters.

We will also need to use the unit vector of the resulting force from the previous section.

unit_vec :: Vector2 Double -> Vector2 Double

unit_vec v | magnitude v == 0 = (V2 0 0)

| otherwise = scale (1 / (magnitude v)) vFor a box initally at rest:

We let this function compute the friction. If the magnitude of the friction is greater than the magnitude of the resulting force without friction, it means the box will stand still or that the magnitudes can be treated as equally big.

ff :: Vector2 Double -> Scalar -> Scalar -> FricConst -> Vector2 Double

ff fr magn_l_ magn_fr u = scale magn_fric (negate (unit_vec fr))

where

magn_fric | magn_l_ * u > magn_fr = magn_fr

| otherwise = magn_l_ * uNow we just need to add the friction vector to our old \(\dot F_{r}\). We call this function fru, from the constant \(\mu\):

fru :: Vector2 Double -> Angle -> FricConst -> Vector2 Double

fru fa a u = (fr fa a) + (ff (fr fa a) magn_l_ magn_fr u)

where

magn_l_ = magnitude (f_l_ fa a)

magn_fr = magnitude (fr fa a)Testing for \(u = 0\). In this case both “fr” and “fru” should give the same resulting vector:

They should also give the same if the incline is flat.

Lastly one should see the edge case where the angle is \(\frac{\pi}{4}\). The magnitude of the normal and the resulting force from the previous section becomes the same (try and control it!). This also means that if \(\mu_{static} = 1\) the magnitude of the friction force becomes \(equal\) to the magnitude of the resulting force without friction. The consequence of this will be that the friction force is just enough to prevent the box from sliding. If we increase the angle just a little, the box starts sliding.

In this case it may be beneficial to see more decimals, given that it should slide more downwards (down on the y-axis) than to the left (left on the x-axis).

Friction for a box in motion:

This one is for you to solve. A box in motion is always affected by the friction (except for one particular edge case).